Clinical Judgement: Let’s Think About Thinking

- -

By Laura M. Cascella, MA

If you’ve ever heard someone use the phrase, “it was a judgment call,” you probably assumed that the person made a decision based on the best available information. That is, the person assessed the situation, considered relevant data, and came to a conclusion based on factual information and his or her own opinion.

The term “clinical judgment” refers to a similar process, namely “the application of information based on actual observation of a patient combined with subjective and objective data that lead to a conclusion.”1 A 2011 article in the Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice explains that “Clinical judgment is developed through practice, experience, knowledge and continuous critical analysis. It extends into all medical areas: diagnosis, therapy, communication and decision making.”2

Because clinical judgment is a complex process that involves various cognitive functions, it’s easy to understand why it is the driving force behind the majority of diagnosis-related malpractice allegations for both physicians and dentists. Further, the prevalence of clinical judgment issues is almost surely tied to the fact that they tend to be less amenable to “simple” fixes than other contributing factors, such as system failures.

This article will (a) take a closer look at the various judgment issues that contribute to diagnosis-related malpractice claims, (b) examine how cognition shapes clinical reasoning and decision-making, (c) discuss how cognitive errors in judgment can occur during the diagnostic process, and (d) explore proposed solutions and risk strategies for managing clinical judgment issues.

Clinical Judgment in the Context of Malpractice

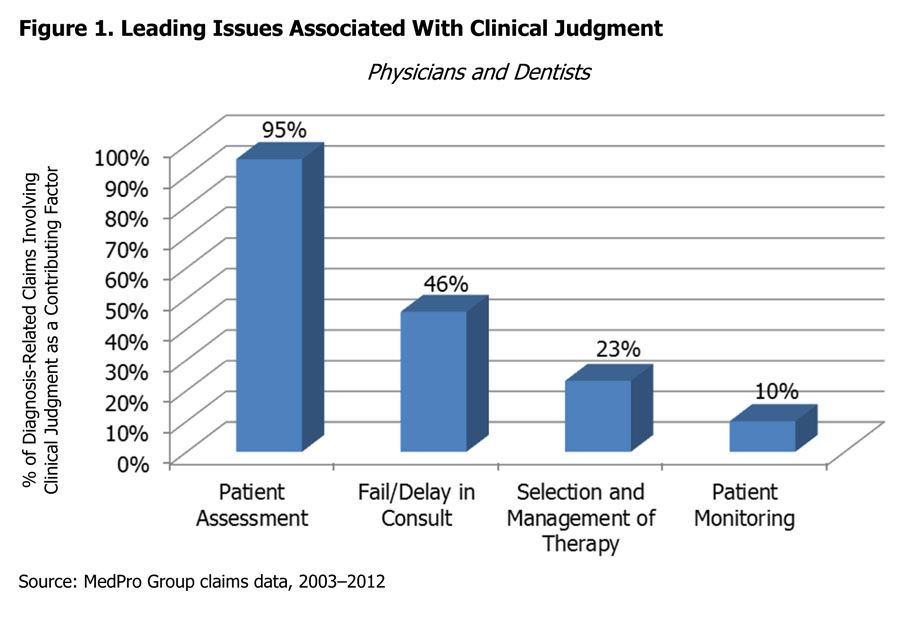

The concept of clinical judgment as a contributing factor to malpractice claims can be difficult to grasp because of its enormity. Simply stated, clinical judgment is a broad category that includes the clinical areas shown in Figure 1

Within clinical judgment, patient assessment issues rise to the top for physicians and dentists. Common examples of patient assessment issues are:

- Failure or delay in diagnostic testing

- Failure to establish a differential diagnosis

- Maintaining a narrow diagnostic focus

- Lack of, or inadequate, patient history and physical

- Failure to rule out or act on abnormal findings

- Misinterpretation of diagnostic test results

The other categories included in clinical judgment are failure or delay in obtaining a consultation, selection and management of therapy, and patient monitoring. Issues related to selection and management of therapy are heavily focused on choosing an appropriate plan of care, including procedural care. This category also includes issues with ordering medications appropriate for the patient’s condition. Allegations associated with patient monitoring mainly involve monitoring a patient’s response to a treatment plan.

Although these examples help define the ways in which clinical judgment errors may contribute to malpractice claims, they don’t explain why these circumstances happen. What causes these missteps and lapses in judgment? Understanding the clinical reasoning and decision-making processes can help explain why clinical judgment so frequently contributes to diagnostic errors.

Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making

When making diagnoses, doctors must “reframe patient symptoms into clinical problems” and attempt to solve these problems, which “may not be unambiguously true or false.”3 Much of the literature focusing on diagnostic errors and clinical reasoning recognizes the dual decision-making model as the basis for clinicians’ diagnostic process.

The dual decision-making model consists of two types of clinical reasoning: Type 1 and Type 2. In Type 1, the reasoning process is automatic, intuitive, reflexive, and nonanalytic. The doctor arranges patient data into a pattern and arrives at a working diagnosis based on previous experience and/or knowledge. In Type 2, the reasoning process is analytic, slow, reflective, and deliberate. This type of thinking is often associated with cases that are complex or with which the doctor is unfamiliar.4,5

Type 1 and Type 2 are not mutually exclusive, and doctors tend to use both, depending on the circumstance. However, research suggests that most clinical work involves Type 1 reasoning.6 Although the automatic, intuitive processes that occur in Type 1 are a requisite part of the thought process and often very effective, they also are vulnerable to cognitive errors.

A variety of cognitive errors can occur as part of the clinical reasoning process. Describing each is beyond the scope of this article; however, the following section attempts to summarize, at a high level, some of the common types and sources of these errors.

Cognitive Errors

Research about the cognitive aspect of diagnostic errors suggests that errors in clinical reasoning often arise from several sources, including knowledge deficits, cognitive biases/faulty heuristics, and affective influences.7

Knowledge Deficits

Gaps in knowledge and clinician inexperience might seem like a logical cause of diagnostic errors. Thus, an individual might easily assume that younger, less practiced doctors would be more susceptible to diagnostic pitfalls.

In reality though, “The majority of cognitive errors are not related to knowledge deficiency but to flaws in data collection, data integration, and data verification,”8 with “data” referring to clinical information obtained during the doctor–patient encounter.

Further, many diagnostic errors are associated with common diseases and conditions, suggesting that other problems with clinical reasoning — such as faulty heuristics, cognitive biases, and affective influences — are the more likely culprit (as opposed to poor knowledge).

Faulty Heuristics and Cognitive Biases

The term “heuristics” refers to mental shortcuts in the thought process that help conserve time and effort. These shortcuts are an essential part of thinking, but they are also prone to error. Cognitive biases occur when heuristics lead to faulty decision-making.9 Some common biases included anchoring, availability, and overconfidence.

Anchoring

Anchoring refers to a snap judgment or tendency to diagnose based on the first symptom or lab abnormality. Anchoring is closely related to several other biases, including:

- Under-adjustment, which is the inability to revise a diagnosis based on additional clinical data

- Premature closure, which is the termination of the data-gathering process (e.g., patient history, family history, and medication list) before all of the information is known

- Primacy effect, which is the tendency to show bias toward initial information

- Confirmation bias, which occurs if a clinician manipulates subsequent information to fit an initial diagnosis

Availability

The availability bias can occur if a clinician considers a diagnosis more likely because it is forefront in his or her mind. Past experience and recent, frequent, or prominent cases can all play a role in availability bias.

For example, a doctor who has recently diagnosed an elderly patient with dementia might be more likely to make the same diagnosis in another elderly patient who has signs of confusion and memory loss — when, in fact, the patient’s symptoms might be indicative of another problem, such as vitamin B12 deficiency.

Overconfidence Bias

This bias refers to “over-reliance on one’s own ability, intuition, and judgment.”10 Overconfidence might result from a lack of feedback related to diagnostic accuracy, which may in turn cause clinicians to overestimate their diagnostic precision. As such, researchers suggest that overconfidence might increase as a doctor’s level of expertise increases.11

Affective Influences

Whereas cognitive biases are lapses in thinking, the term “affective influences” refers to emotions and feelings that can sway clinical reasoning and decision-making.12 For example, preconceived notions and stereotypes about a patient might influence how the doctor views the patient’s complaints and symptoms.

If the patient has a history of substance abuse, for instance, the doctor might view complaints about pain as drug-seeking behavior. Although this impulse might be accurate, the patient could potentially have a legitimate clinical issue.

Additionally, certain factors might trigger negative feelings about a patient that can cause the clinician to inadvertently judge or blame the patient for his or her symptoms or condition. For example, a patient’s obesity might be attributed to laziness or general disregard for his or her health. Or, a patient who is noncompliant with follow-up care might be viewed as difficult — in reality, though, the noncompliance might be related to financial issues.

In a 2008 article titled “Why Doctors Make Mistakes,” Dr. Jerome Groopman discusses how negative feelings can lead to attribution bias, a type of affective influence. Dr. Groopman notes that this type of bias accounts for many diagnostic errors in elderly patients. For example, clinicians might have a tendency to attribute elderly patients’ symptoms to advancing age or chronic complaining, rather than exploring other potential causes.13

Positive feelings about patients also can affect diagnostic decisions. In outcome bias, for example, a doctor may overlook certain clinical data in order to select a diagnosis with better outcomes. By doing so, the doctor is placing more value on what he or she hopes will happen, rather than what might realistically happen.

In addition to positive and negative feelings about patients, clinician and patient characteristics — such as age, gender, socio-economic status, and ethnicity — also can affect the diagnostic process. Consider that research has suggested that women are less likely than men to have complaints about pain taken seriously, and they are less likely than men to received aggressive treatment for pain.14

A variety of other factors also can affectively influence a doctor’s reasoning, such as:

- Environmental circumstances, e.g., high levels of noise or frequent interruptions

- Sleep deprivation, irritability, fatigue, and stress

- Mood disorders, mood variations, and anxiety disorders15

The complex interaction between these influences and cognitive biases can have a profound effect on clinical reasoning and decision-making, which in turn can lead to various lapses in clinical judgment.

Proposed Solutions

Although cognitive processes are well-studied, further research is needed to determine how best to prevent the flaws in clinical judgment that can lead to diagnostic errors. A number of strategies and solutions have been proposed, which range from the use of diagnostic aids, to process changes, to debiasing techniques.

For example, some researchers suggest that the use of evidence-based decision support systems, clinical guidelines, checklists, and clinical pathways can help support the clinical reasoning and decision-making processes. However, they note that although these tools can be useful, “unless they are well integrated in the workflow, they tend to be underused.”16

Additionally, incorporating a diagnostic review process into the workflow pattern might be helpful. The review may include timeouts to consider and reflect on working diagnoses, as well as the solicitation of second opinions.

A variety of techniques to reduce cognitive bias and affective influences have also been proposed, including training in situational awareness and metacognition, so that clinicians can think critically about their own thought processes and how biases might affect them. These techniques may include cognitive forcing functions, which are strategies designed to help clinicians self-monitor decisions and avoid potential diagnostic pitfalls.17

Although many of these techniques show promise, more research is needed to evaluate their efficacy and to determine the feasibility of introducing them into busy practice environments.

Risk Management Strategies

As researchers continue to explore long-term solutions to errors in clinical judgment, doctors can proactively implement strategies to help mitigate risks associated with clinical reasoning, cognition, and decision-making. The following list offers broad suggestions for managing these risks within medical and dental practices.

- Perform complete patient assessments, including establishment of a differential diagnosis, appropriate consideration of diagnostic testing, and careful review of test results.

- Update and review patients’ medical histories, problem lists, medication lists, and allergy information on a regular basis.

- Implement and utilize clinical pathways to standardize processes and support quality care.

- Consider the use of decision support systems, diagnostic timeouts, consultations, and group decision-making to support clinical reasoning.

- Formalize procedures for over-reads of diagnostic tests and imaging, peer review and quality improvement, use of diagnostic guidelines, and better access to patients’ records.

- Be aware of common cognitive biases and how they might negatively affect clinical judgment.

- Consider group educational opportunities that allow doctors to explore cognitive biases and form working solutions together.

Conclusion

Although diagnostic errors have a number of root causes, clinical judgment is by far the most common contributing factor. The complex nature of clinical reasoning and decision-making makes it vulnerable to cognitive biases and affective influences. These errors can subconsciously lead to lapses in judgment, which in turn can cause diagnostic mistakes.

More studies are needed to determine effective approaches for addressing cognitive errors. However, a number of strategies — such as decision support systems, clinical pathways, checklists, reflective practice, and cognitive awareness — show promise. By considering how these strategies can be implemented in everyday clinical activities, physicians and dentists can begin to take steps toward managing diagnostic risks.

Endnotes

1 http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/clinical+judgment

2 Kienle, G. S., & Kiene, H. (2011, August). Clinical judgment and the medical profession. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 17(4), 621–627.

3 Phua, D. H., & Tan, N. C. (2013). Cognitive aspect of diagnostic errors. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 42(1), 33–41.

4 Nendaz, M., & Perrier, A. (2012, October). Diagnostic errors and flaws in clinical reasoning: Mechanisms and prevention in practice. Swiss Medical Weekly, 142:w13706.

5 Ely, J. W., Graber, M. L., & Crosskerry, P. (2011, March). Checklists to reduce diagnostic errors. Academic Medicine, 86(3), 307–313.

6 Nendaz, et al., Diagnostic errors and flaws in clinical reasoning; Crosskerry, P., Singhal, G., & Mamede, S. (2013, October). Cognitive debiasing 1: Origins of bias and theory of debiasing. BMJ Quality & Safety, 22(Suppl 2), ii58–ii64.

7 Phua, et al. Cognitive aspect of diagnostic errors.

Clinical Judgment: Let’s Think About Thinking 9

8 Nendaz, et al., Diagnostic errors and flaws in clinical reasoning.

9 Phua, et al. Cognitive aspect of diagnostic errors.

10 Pilcher, C. A. (2011, March 31). Diagnostic errors and their role in patient safety. MedPage Today. Retrieved from http://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2011/03/diagnostic-errors-role-patient-safety.html

11 Clark, C. (2013, August 27). Physicians’ diagnostic overconfidence may be harming patients. HealthLeaders Media. Retrieved from http://www.healthleadersmedia.com/content/QUA-295686/Physicians-Diagnostic-Overconfidence-May-be-Harming-Patients##; Phua, et al., Cognitive aspect of diagnostic errors.

12 Crosskerry, P., Abbass, A. A., & Wu, A. W. (2008, October). How doctors feel: Affective influences in patient’s safety. Lancet, 372, 1205–1206; Phua, et al. Cognitive aspect of diagnostic errors.

13 Groopman, J. (2008, September/October). Why doctors make mistakes. AARP Magazine, p. 34.

14 Hoffman, D. E., & Tarzian, A. J. (2001). The girl who cried pain: A bias against women in the treatment of pain. Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics, 29, 13-27.

15 Crosskerry, P., et al., How doctors feel.

16 Ely, et al., Checklists to reduce diagnostic errors.

17 Crosskerry, P. (2003). Cognitive forcing strategies in clinical decisionmaking. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 41, 110–120.

The information provided in this document should not be construed as medical or legal advice. Because the facts applicable to your situation may vary, or the regulations applicable in your jurisdiction may be different, please contact your attorney or other professional advisors if you have any questions related to your legal or medical obligations or rights, state or federal statutes, contract interpretation, or legal questions.

The Medical Protective Company and Princeton Insurance Company patient safety and risk consultants provide risk management services on behalf of MedPro Group members, including The Medical Protective Company, Princeton Insurance Company, and MedPro RRG Risk Retention Group.

© MedPro Group.® All Rights Reserved.