Communication as a Contributing Risk Factor in Diagnostic Errors

- -

By Laura M. Cascella, MA

Providing coordinated, competent patient care involves precision at many points in the clinical process, but particularly in sending and receiving information. Yet, “the increasingly complex healthcare environment can complicate the communication process and hinder the information exchanges necessary for optimum care.”1

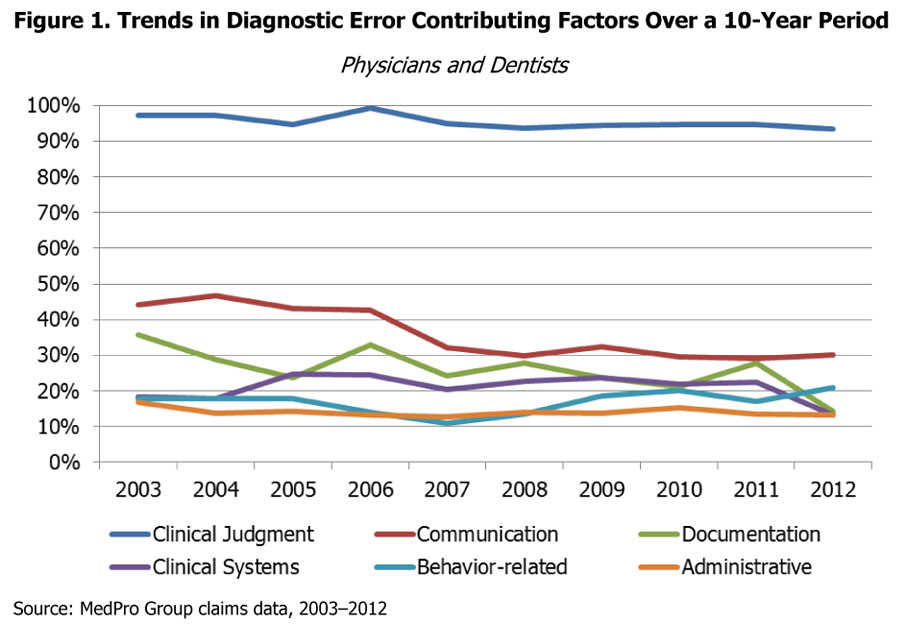

Communication breakdowns in healthcare are not uncommon, and they can result in anything from minor confusion to serious patient harm. When evaluating diagnostic errors, communication issues are the second most common contributing factor in malpractice claims, based on MedPro Group claims data.

Although MedPro Group’s data show that communication issues have decreased over time, they still remain a persistent factor in claims and occur at a palpable rate (see Figure 1).

In a broad sense, communication failures can be broken down into two main categories: communication issues among providers (and their staff members) and communication lapses between providers and patients. This article will examine both and will discuss various ways in which practitioners can implement safeguards in their communication processes.

Communication Issues Among Healthcare Providers and Staff Members

Successful communication among healthcare providers and between providers and their staffs has always been a critical element of patient safety. The emphasis on communication has been even more pronounced in recent years, with the shifting focus toward collaborative and team-based care. For example, the Institute of Medicine lists communication as one of the five core principles guiding new models of care delivery.2

However, even as the demand for collaborative care increases, communication still remains a top risk issue in healthcare practices. Further, “legal dangers appear to be on the rise as team-based care grows and patients are handed off to a wider scope of health professionals.3

In terms of diagnosis, certain elements of the patient care process might be particularly vulnerable to communication missteps and errors, such as coordination of care or transitions of care among multiple providers and medical staff. These providers and staff members might be working in the same practice or coordinating care across various organizations. Further, the scenario in which information is exchanging hands can vary. For example, a provider might be providing coverage for another clinician, ordering diagnostic procedures, referring a patient to a specialist (or receiving a referral), or participating in multidisciplinary care.

Regardless of the situation, care coordination and care transitions require careful communication among providers and healthcare facilities, accountability for assigned roles, ownership of established processes, and engagement with providers and patients.4 When evaluating your practice’s efforts to support continuity and coordination of care, consider whether policies are in place that:

- Define the specific types of information to communicate during care coordination or transitions of care, such as the patient’s medical history, family history, known conditions, allergies, medication list, and treatment information.

- Clearly establish duty of care and clinical responsibilities for all providers. For example, who is communicating information to the patient?

- Support thorough and ongoing communication between doctors, advanced practice providers, and clinical staff (through electronic mediums, regularly scheduled meetings, etc.).

- Define appropriate processes for referrals and consultations, such as how the practice intends to handle urgent communication, consultation reports, informed consent, and follow-up.

- Outline a plan for communication of pertinent clinical findings or critical test results.

- Establish requirements for using tools, checklists, and forms as part of the care coordination process.

- Define expectations for documentation in the patient record.

Because care coordination involves many components and individuals, as well as complex logistical processes, healthcare providers may feel limited in their ability to manage all of the moving parts and effect change — especially when working with individuals and groups outside of their practices.

However, taking steps within the practice to address gaps in, and enhance policies related to, care transitions and continuity of care can make a difference. A 2014 Medical Economics article notes that practitioners can “build a rigorous transition of care process”5 within their organizations by implementing proactive strategies. Examples of these strategies include formalizing inbound patient referral processes, focusing on the logistics of external referrals, and finding opportunities to improve collaboration with other providers.

Communication Issues Between Providers and Patients

Communicating well with patients is vital in establishing a culture of safety, creating a successful provider–patient partnership, and engaging patients in shared responsibility for their care.

Failures or gaps that occur in provider–patient communication may increase the likelihood of errors, including diagnostic errors. Further, some malpractice studies suggest that providers who are poor communicators are more likely to be sued. A study in Florida showed that the way in which patients perceive doctors’ “interest, accessibility, and communications ability was more important than the technical quality of care as a predictor of the physician’s malpractice claiming experience.”6

Thus, the ability to effectively interact with patients is essential in all steps in the care process — from initial encounter through follow-up.

Communication Policies

To help mitigate the risk of poor communication with patients, healthcare providers should consider developing comprehensive policies related to verbal, electronic, and written communication with patients. These policies should:

- Establish expectations for courteous, respectful communication that is reflective of a patient-centric, service-oriented culture.

- Describe the purpose and accepted use of each type of communication and explicitly note the preclusion of certain activities (such as diagnosing over the phone or email).

- Set forth standards and criteria for telephone triage that (a) support scheduling based on patient needs, (b) establish the use of boilerplate responses and scripts (when appropriate), and (c) assign roles for clinical and nonclinical staff.

- Define the appropriate use of email and social media for communicating with patients, including management of accounts, development of disclaimer language, and staff roles.

- Establish appropriate timeframes for clinician response to verbal and electronic inquiries and concerns.

- Outline steps for managing patient complaints and measuring patient satisfaction (for example, through the use of surveys).

- Delineate a process and appropriate timeframes for following up with patients about test results and missed or cancelled appointments.

- Define specific requirements for documenting patient interactions within the patient’s record.

- Support staff education and training on communication procedures and techniques.

Provider–Patient Encounters

A 2013 study that focused on the types and origins of diagnostic errors in primary care found that more than 75 percent of the process breakdowns that led to diagnostic errors involved the provider–patient encounter.7

What goes wrong during these interactions? Although it’s not always clear, various office-, practitioner-, and patient-related circumstances can play a role, such as:

- Environmental factors, e.g., ongoing distractions or interruptions.

- Situations in which patients do not feel comfortable reporting their symptoms or medical histories.

- Circumstances in which providers prematurely cut off patients while they’re talking. Research has shown that, on average, doctors will interrupt patients within the first 18 seconds of telling their story.8

- Situations in which patients or their family members feel that their healthcare providers are devaluing their views or failing to understand their perspectives.

These issues, alone or in combination, can lead to communication breakdowns, problems with data collection and synthesis, patient dissatisfaction, and — ultimately — diagnostic mistakes.

Tackling provider–patient communication issues can be tricky due to the somewhat nebulous nature of these problems. However, various techniques and strategies can be employed to enhance interactions with patients, build better provider–patient partnerships, and engage patients in the diagnostic process.

Although these strategies will not eliminate the potential for miscommunication, they may help providers (a) improve their processes for gathering information, (b) build patient trust, and (c) reinforce a culture of safety — critical elements for improving the diagnostic process, reducing the risk of errors, and preventing liability claims.

Strategies to Enhance Communication During the Provider–Patient Encounter

- Allow adequate time for dialogue, and take the time to understand the patient’s/family’s concerns and point of view.

- Make an effort to allow patients to fully voice their concerns without interruption.

- Repeat key information back to the patient after he or she has finished explaining the chief complaint or reason for the visit.

- Determine what the patient hopes to achieve as a result of the visit.

- Whenever possible, sit down with the patient while taking his or her history or reviewing clinical information.

- Ask open-ended questions to generate more thorough information. For example, “So, you’re having pain?” becomes “Can you tell me more about your pain?”

- Create an atmosphere that encourages questions and open dialogue. Specifically ask whether the patient has questions or would like to offer any additional information before the appointment concludes.

- Use eye contact in face-to-face conversation. Eye contact is increasingly more important as technologies, such as electronic health records (EHRs), are used in the office practice environment.

- Consider your body language and how a patient might perceive it. For example, fidgeting or constantly looking at a computer screen might be construed as dismissive. Certain facial expressions might be considered judgmental, which may cause the patient to withhold information.

Patient Comprehension

A major obstacle in provider–patient communication is ensuring patient comprehension of both verbal and written health information, including clinical explanations, recommendations, instructions, educational materials, and more.

Health information and services often are unfamiliar and confusing, and people of all ages, races, cultures, incomes, and educational levels may struggle with health literacy. In fact, the Institute of Medicine says that nearly half of all American adults have trouble understanding and acting on health information.9

Further, the CDC explains that almost 90 percent of adults have difficulty using the everyday health information that is routinely available in healthcare facilities.10

In addition to limited health literacy, other issues — such as language barriers and auditory, visual, or speech disabilities — can hinder the communication process and patient understanding.

Because “obtaining, communicating, processing, and understanding health information and services are essential steps in making appropriate health decisions,”11 gaps in these areas can have serious implications for informed consent/refusal, patient follow-up, and patient compliance.

Thus, taking steps to ensure patient understanding and awareness is critical to your practice’s communication strategies. This checklist can help you identify patient comprehension strategies already at work in your practice and target areas for improvement.

Note: As with other aspects of the patient care process, activities related to informed consent discussions, consultative advice, clinical recommendations, and patient education should be documented in the patient record.

Conclusion

Dr. Jerome Groopman, in his book titled How Doctors Think, states that although “modern medicine is aided by a dazzling array of technologies . . . language is still the bedrock of clinical practice.”13 This sentiment holds true when examining the ways in which communication gaps or failures contribute to diagnostic errors and subsequent malpractice claims.

Although MedPro Group data show that communication considerably trails clinical judgment as a contributing factor in diagnosis-related claims, it nonetheless represents a consequential risk. Healthcare practices can potentially mitigate that risk by evaluating collaborative processes among providers, carefully considering communication processes between providers and staff and providers and patients, and developing policies to strengthen and safeguard communication efforts.

Endnotes

1 ECRI Institute. (2014, January). Communication. Healthcare Risk Control (Suppl A).

2 Mitchell, P., Wynia, M., Golden, R., McNellis, B., Okun, S., Webb, C. E., . . . Von Kohorn, I. (2012). Core principles & values of effective team-based health care. Institute of Medicine. Retrieved from http://www.iom.edu/Global/Perspectives/2012/TeamBasedCare.aspx

3 Gallegos, A. (2014, July 15). Medical liability: Missed follow-ups a potent trigger of lawsuits. American Medical News. Retrieved from http://www.amednews.com/article/20130715/profession/130719980/2/

4 Woodcock, E. W. (2014, March). Seven steps for managing transitions of care. Medical Economics. Retrieved from http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/news/seven-steps-managing-transitions-care?page=full

5 Ibid.

6 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2002, September). Counseling of physicians at high risk of malpractice claims lowers the level of patient complaints. Retrieved from http://www.rwjf.org/reports/grr/033572.htm

7 Singh, H., Giardina, T. D., Meyer, A. N., Forjuoh, S. N., Reis, M. D., & Thomas, E. J. (2013, March 25). Types and origins of diagnostic errors in primary care settings. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(6), 418–425

8 Levine, M. (2004, June 1). Tell the doctor all your problems, but keep it to less than a minute. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2004/06/01/health/tell-the-doctor-all-your-problems-but-keep-it-to-less-than-a-minute.html

9 Nielsen-Bohlman, L., Panzer, A. M., & Kindig, D. A. (Eds.). (2004). Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

10 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Health literacy: Learn about health literacy. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn/index.html

11 Ibid.

12 PlainLanguage.gov. (n.d.). What is plain language? Retrieved from http://www.plainlanguage.gov/whatisPL/index.cfm

13 Groopman, J. (2007, March 15). Excerpt: How doctors think. NPR Books. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/2007/03/16/8946558/groopman-the-doctors-in-but-is-he-listening#8894868

The information provided in this document should not be construed as medical or legal advice. Because the facts applicable to your situation may vary, or the regulations applicable in your jurisdiction may be different, please contact your attorney or other professional advisors if you have any questions related to your legal or medical obligations or rights, state or federal statutes, contract interpretation, or legal questions.

The Medical Protective Company and Princeton Insurance Company patient safety and risk consultants provide risk management services on behalf of MedPro Group members, including The Medical Protective Company, Princeton Insurance Company, and MedPro RRG Risk Retention Group.

© MedPro Group.® All Rights Reserved.